30-Year Construction Trends Part 1: The Retail Apocalypse

The Mall is Dead, Long Live the Warehouse

This post is the first of a three-part (at least) series that uses construction spending data to look at how and why the industry has changed over the past thirty years. Part 2 will be about manufacturing-related construction, and part 3 will look at state level construction spending trends. While Part 1 is free for everyone, Parts 2 and 3 will only be for paying subscribers.

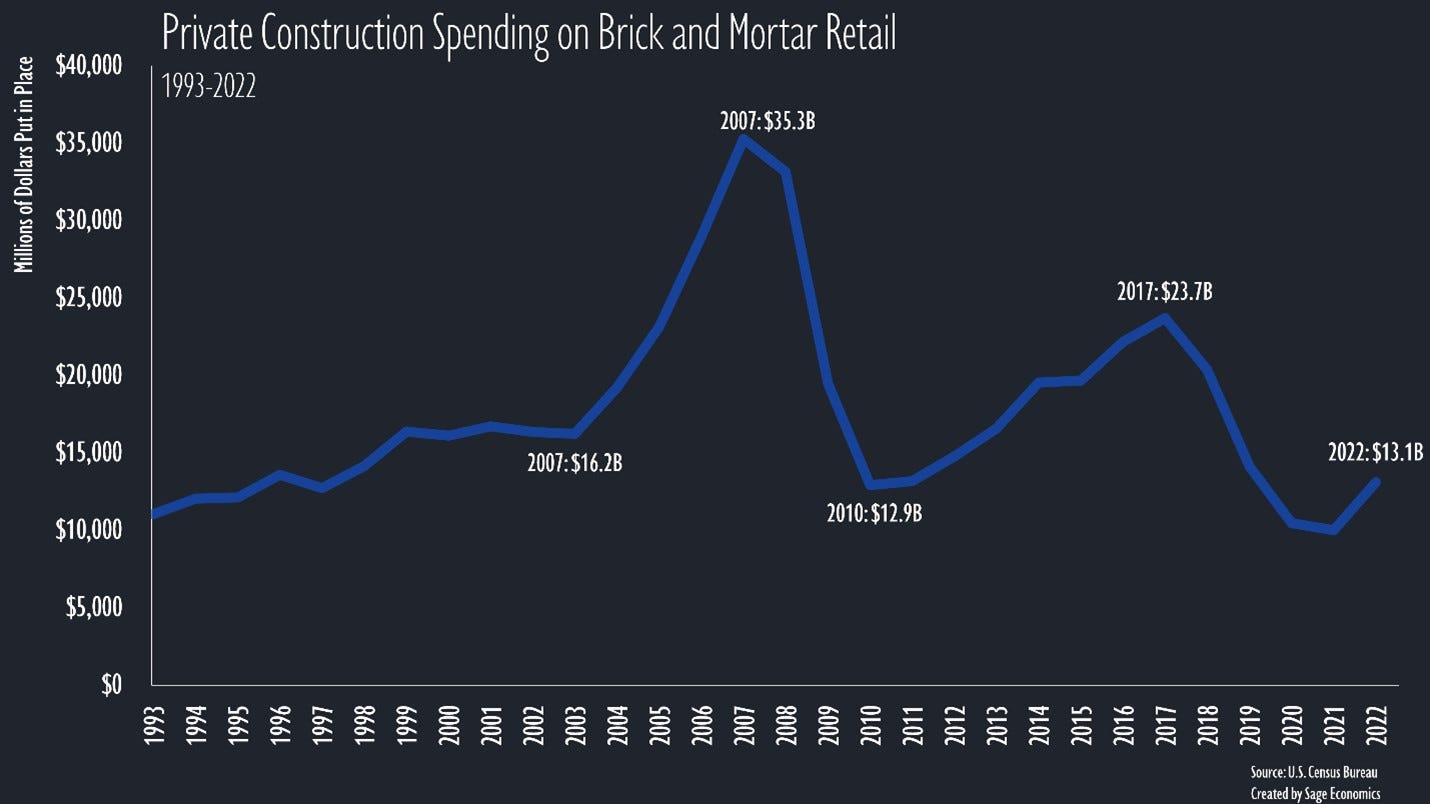

Investment in brick and mortar retail, after a decade of steady growth from 1993 to 2003, took off in the early 2000s. Construction spending in the segment surged 117% over a five-year period and peaked at $35 billion in 2007. Then the Great Recession devastated the segment from 2008-2010, bringing on the dawn of the The Retail Apocalypse.

As is often the case, it happened slowly at first and then all at once in 2017, a year when over 12,000 physical stores closed. This had an immediate and profound impact on construction spending on brick and mortar retail structures.

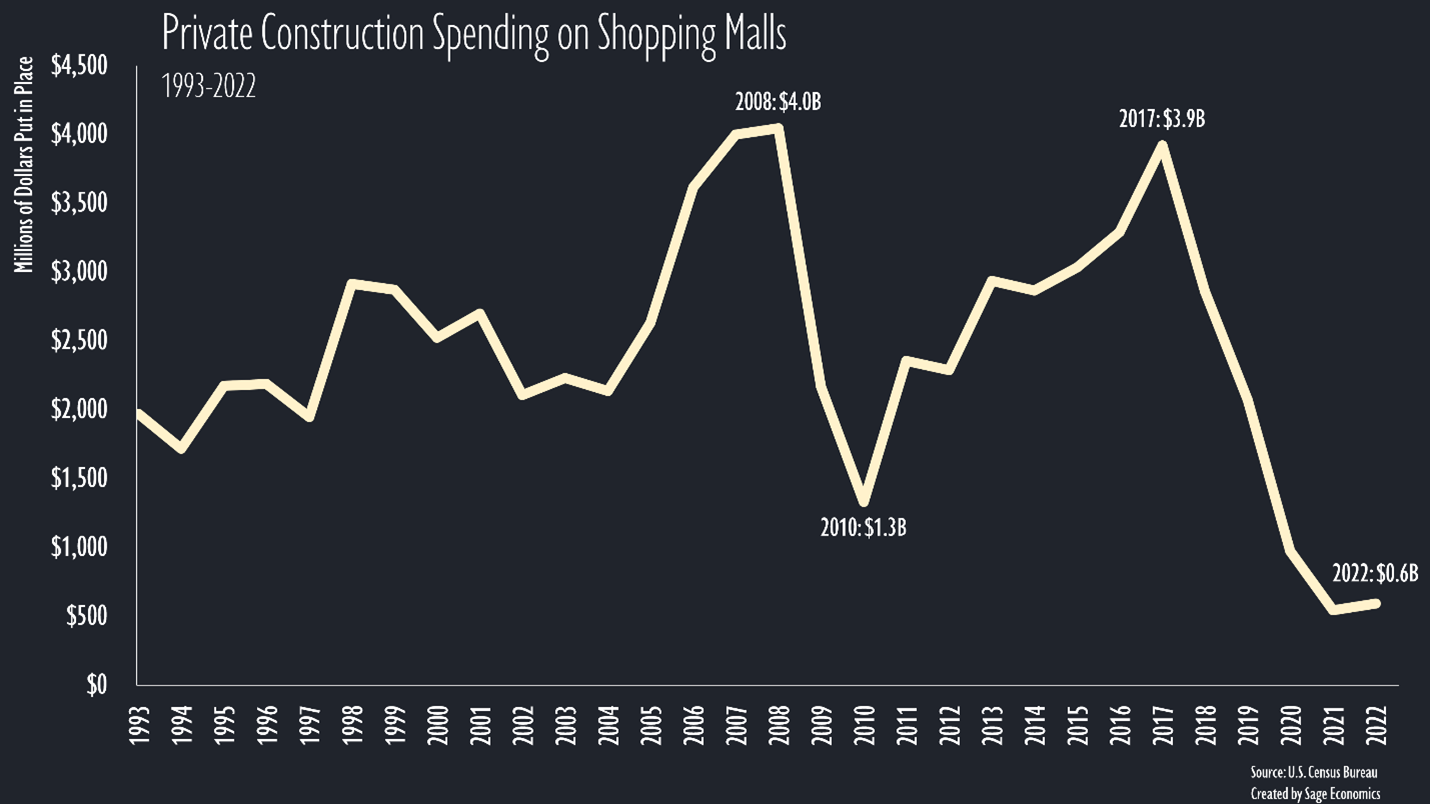

Malls were the first and biggest victim of the Retail Apocalypse (I would have called it the “retailpocalypse,” but that’s just me). Big box stores like Lord & Taylor, JCPenney, and others declared bankruptcy. So did smaller mall staples like J. Crew and RadioShack.

As a result, construction spending on shopping malls fell from about $4 billion in 2008 to less than $600 million in 2022 (and this isn’t adjusted for inflation). To put this into context, we spent 230% more on the construction of shopping malls in 1993 than we did in 2022.

While the shopping mall is the best known victim of E-Commerce, every brick and mortar retail segment saw less investment in 2022 than in 2008—again, that’s without accounting for inflation. Construction spending on shopping centers (think strip malls and town centers) is down more than 52% from the cyclical peak in 2008. Spending on department stores (-50%) and drug stores (-74%) has also cratered over the past 15 years.

A lot of factors get blamed for the Retail Apocalypse: Millennials spending on experiences instead of things (always need to blame the Millennials), changing professional dress codes, overdevelopment, bad management, inequality, and—the big one—E-Commerce.

At the start of 2008, the year that investment in shopping malls peaked, just 3.6% of total retail sales occurred online. But even then, the inexorable rise of online retailers was well underway.

E-Commerce steadily gobbled up market share over the decade following the Great Recession, briefly surged during the pandemic, and having returned to the pre-pandemic trend, currently accounts for more than 15% of all retail spending.

You might be thinking that a 15% market share shouldn’t be enough to initiate an apocalypse, but that’s 15% of all retail spending, which includes categories like gas stations, restaurants and bars, and car dealerships. If we exclude those three categories, the E-Commerce market share increases to a more significant 27%.

So the cataclysmic death of brick and mortar retail (full disclosure: the apocalyptic language is overstated, but it’s fun to be dramatic about these things) led to a huge decline in brick and mortar construction. Warehouses and distribution space, a necessity for E-Commerce, picked up the slack.

After rising gradually during the 90s and 2000s, construction spending on warehouses blasted off during the 2010s, expanding 1,054% between the start of the decade and 2022.

To put that into context, the private sector now spends more each year on warehouse construction than on the construction of healthcare, educational, and religious structures combined. Construction spending on warehouses accounted for about 15% of the commercial category (also includes car dealerships, farms, stores, and restaurants) in 2010. By 2022, that share stood at 56%.

But these data only goes through 2022, and 2023 has been a bad year for warehouse investment: construction starts on warehouses have now (as of Q3 2023) fallen to the lowest level in over a decade.

This has more to do with high interest rates and economic uncertainty than demand, and while warehouse investment will have its ups and downs in the short term, demographic trends are a tailwind for the segment. Why? Because Millennials are more likely to shop online than Gen Xers, and Gen Xers are more likely to shop online than Baby Boomers. As soon as Gen Zers start making some money, they’ll almost certainly be more likely than Millennials to spend it online.

The upshot is that the warehouse segment’s reign over the commercial construction category should continue through at least the 2020s.

A final note on warehouse construction: it’s not just E-Commerce companies that love to store things. Of the nearly 90 segments tracked by the Census Bureau, none has seen a bigger percentage increase in construction spending over the past 30 years than mini-storage (think self-storage centers), which is up 6,436% since 1993. Yes, it’s still a relatively small category at $5.6 billion in 2022, but that’s 17% more than we spent on shopping malls, department stores, and drug stores combined last year.

What’s Next

Part 2 of this series will be about 30-year trends in manufacturing-related construction spending. That, like our Week in Review Posts every Friday, will only be for paid subscribers. If that’s not you and you want it to be, just click the button below.