The Federal Reserve System (the Fed) increased interest rates a few weeks back. If you know what that means, feel free to stop reading now. Like the title says, this is a very basic primer.

For anyone else, this post, set up as a Q&A (to be clear, no one specifically asked us these questions), explains how and why the Fed raises and lowers interest rates. There are links to most of the key terms in this post.

When you say “interest rates,” what do you mean?

The “interest rate” we’re talking about here is the federal funds rate (FFR), and more specifically, it’s a target range of FFR set by the Fed1. Let’s take a quick step back.

Banks2 need to keep enough cash on hand, or reserves, to meet demand for withdrawals, and when they think their reserves might fall too low, they borrow from another bank that has excess reserves. These loans occur overnight (i.e., are due the following morning), and are also called overnight loans, interbank loans, or overnight federal funds transactions.

The interest rate the lending bank charges the borrowing bank is the federal funds rate (again, FFR), which is also called the interbank rate or the overnight rate. The FFR represents the lowest rate a bank would ever charge on a loan because 1) they’re only loaning it overnight and 2) the borrower is another bank, so it’s as safe as loans get.

Why does the Fed care about the FFR?

Banks keep a certain percentage of their reserves in a Fed account. They used to be legally required to keep those reserves in a non-interest paying account at the Fed, but now the legal requirement is gone and the Fed pays interest on reserves. These reserve funds kept at the Fed are what banks use to make overnight loans, which is why the system of interbank lending is called the federal funds market.

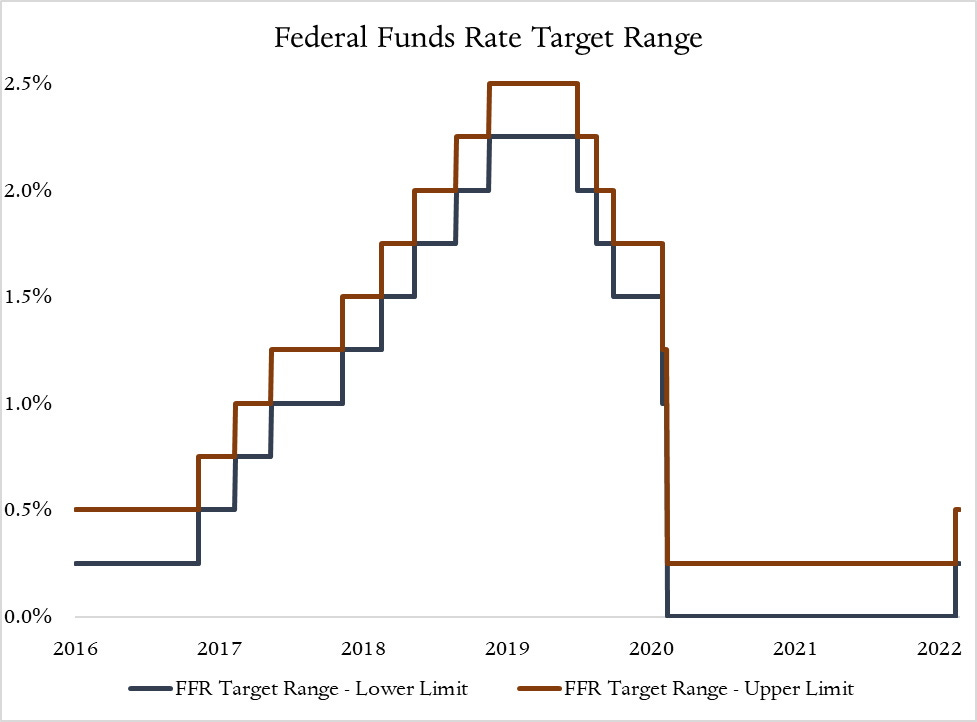

So the Fed establishes a target range for the FFR, and they raise and lower this target range to either stimulate or dampen economic activity. The chart below shows how that target range, which typically spans 0.25 percentage points, has changed over time.

Here’s the general logic behind why the Fed changes the target range of the FFR: if banks have to pay a higher rate on money borrowed overnight from other banks, they’ll also charge a higher interest rate on loans to their customers. When banks charge their customers higher rates, consumers and producers borrow less money, which leads to less economic activity. This is called contractionary monetary policy.

The opposite is also true. If the Fed lowers the target range of the FFR, and banks now pay a lower rate on interbank loans, they’ll also lower the interest rates they charge customers on loans. When banks charge their customers lower rates, producers and consumers borrow more money, which generates more economic activity. This is called expansionary monetary policy.

An example: the pandemic (economically) started in February/March 2020 (March was the first shutdown month). The Fed, and everyone else, realized it was going to be a train wreck for the economy, so they lowered the target range of the FFR from 1.5-1.75%, which it had been for the first two months of 2020, to 0-0.25%. (They also did a bunch of other stuff to prop up the economy, but we’re just talking about interest rates here.)

The lower FFR made it cheaper for banks to borrow from each other. That in turn made banks willing to charge borrowers (producers and consumers) lower interest rates on loans. The average rate for a 30-year fixed mortgage slid below 3% by end of 2020, the lowest level on record, which among other things caused a surge in homebuying. This produced windfalls for sellers and created commercial opportunities for realtors, home remodelers, stagers, title insurers, moving companies, etc. Homeowners with variable rate mortgages also got a break on interest payments.

The lower FFR also decreased the cost of borrowing for businesses. Some borrowed money to stay afloat, others to fund expansions. The point is, more money was borrowed than would have been if rates had been higher.

On the flip side, when the economy seems to be growing too quickly—yes, the economy can grow too quickly, like right now, whereby the demand for goods has increased too rapidly and supply chains and labor markets can’t keep up, causing rampant inflation—the Fed raises the FFR. This makes it more expensive for banks to borrow money from other banks, so banks raise the interest rates they charge their customers. The cost of borrowing increases, which means fewer people and businesses take out loans, which, all else equal, lowers demand and slows economic growth.

It’s all a bit more complicated and nuanced, but this is the general gist.

So the Fed just straight up tells the banks what rate to use?

Haha, no. That would be way too simple.

The Fed sets a target range for the FFR, but the banks involved in a loan actually decide the rate. So the Fed can’t mandate what rate the banks use, but they can influence it, and their primary tool to do so is the interest on reserve balances (IORB) rate. The IORB rate is the rate the Fed pays banks on the reserves they keep in a Fed account.

The FFR gravitates toward the IORB rate because IORB gives banks a risk-free overnight investment, so they won’t lend their reserves in the federal funds market for less than the IORB rate.

However, there are other financial institutions that can have accounts at the Fed but don’t earn IORB. These institutions are willing to lend money to other banks at less than the IORB, because earning some interest on their reserves is better than earning none. The best example of this is federal home loan banks (FHLB), which don’t earn IORB and, as a result, lend a lot in the federal funds market.

To keep the FFR from falling below the target range, the Fed has another tool called the overnight reverse repurchase agreement facility (ON RRP), which is like the IORB but for the financial institutions that don’t earn the IORB (explaining this mechanism is too far into the weeds for this post, but feel free to explore on your own). These non-interest earning financial institutions won’t lend money at a rate lower than the ON RRP rate, because like the IORB, it’s a risk-free overnight investment option.

So the FFR won’t go above the IORB rate, and it won’t go below the ON RRP rate. As a result, the effective FFR—the volume weighted median interbank rate across all transactions—tends to be just slightly lower than the IORB and slightly higher than the ON RRP rate. Because the Fed directly sets both of those rates, it can effectively maneuver the FFR into the target range.

The table below shows what happened with the recent rate hike. The Fed increased the target range of the FFR, and to influence banks to use that FFR, they raised the IORB rate and the ON RPP rate. As a result, the effective FFR increased from 0.08% to 0.33%.

Has it always worked like this?

No. Around 2008 monetary policy changed from a limited-reserve framework to an ample-reserve framework. Under the old framework, the Fed’s primary policy tools were open market operations and reserve requirements, while today their key tools are the IORB and ON RRP rates. If you’re interested, this is a great primer from the St. Louis Fed.

Why is the Fed raising rates now?

The Fed’s job is to “promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates,” and if you’ve haven’t heard, we’re experiencing a bit of inflation at the moment (which is to say, prices are in no way stable). Consumer prices, as measured by the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Price Index, are up 7.9% from February 2021 to February 2022. That’s the largest year-over-year increase in 40 years.

There are a lot of causes for the current bout of inflation, but a big one is outsized demand for goods. Since the start of the pandemic, personal expenditures on goods are up nearly 25% while personal expenditures on services are up just a bit less than 8%. Supply chains, which were already having a pretty bad time with the pandemic, buckled under the literal weight of that new washing machine you ordered.

This has caused the demand for workers to surge as producers try to make enough stuff to satisfy demand. The U.S. currently has 11.3 million job openings, about 57% more than we had at the start of 2020, and the unemployment rate is at 3.8%, which is lower than at any point from 1970-2017.

Put simply, demand is too high for our suppliers and labor markets, and that’s making prices go up. The Fed is now trying to fix this by raising the target range of the FFR. As the cost of interbank lending goes up, the cost of borrowing money will increase, fewer people and businesses will borrow, demand will go down, supply chains and labor markets will catch up, and inflation will subside.

That’s the idea, anyway.

If raising rates lowers inflation, why aren’t they raising rates faster?

You might have heard the term “soft landing” thrown around lately, as in the Wall Street Journal’s “The odds don’t favor the Fed’s soft landing,” MarketWatch’s “Soft landing? Activist investor Carl Icahn sees ‘recession or even worse’ ahead for the U.S.,” or CNN’s “The Fed is targeting a soft landing. Getting it wrong means recession.” The economy is the metaphorical plane the Fed is trying to land, and if they come in too steep the whole thing will crash and burn, causing a recession.

Taking a gradual approach gives the Fed the flexibility to adjust their strategy; if hiring dwindles, they can pull back, and if we keep adding 620,000 jobs per month (the average monthly growth since the start of 2021) but inflation remains too high, they can raise rates higher/sooner than planned.

The task (suppressing inflation without causing a recession) looked a lot easier before Russia invaded Ukraine—appropriate that landing a plane during a war is more difficult—which has stressed out supply chains and pushed inflation higher.

The Fed has raised rates once this year by 25 basis points (1 basis point=0.01 percentage points) and anticipates the equivalent of 6 more 25-point increases by the end of 2022. If all goes as currently planned, the target range of the FFR would be 1.75-2.0% at the end of the year, which is the same range as in October 2019.

Wrapping up

Here’s a quick summary:

The Fed sets a target range for the interest rates banks charge other banks (the FFR) when lending out their reserve balances.

When the FFR goes up, the interest rates banks charge their customers go up too.

Higher interest rates → less money borrowed → less economic activity → inflation goes down

When the FFR goes down, the interest rates banks charge their customers go down too.

Lower interest rates → more money borrowed → more economic activity → employment goes up

The Fed steers the FFR into the target range using the IORB and ON RRP rates.

That’s all we’ve got—hope this helped. Send us questions, comments, etc., and let us know what other topics you’d like us to tackle with one of these very basic primers.

As always, recall that you can become a paid subscriber to get access to our Week in Review posts that are sent out every Friday (as well as other special content). The more paid subscribers we have, the more time we have to generate content like this.

We’re going to say “Fed” a lot in this post, but sometimes we mean different parts of the Fed. For instance, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is responsible for open market operations, while the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System is responsible for things like setting the discount rate and the interest on reserve balances. You can read more here.

We’re going to use “banks” instead of “depository institutions” in most instances, though technically we mean the latter which can also include credit unions, mortgage loan companies, etc.

Excellent Primer, Anirban. Thank you.