Like a Bad First Date, September Payroll Report Disappoints

There are Several Candidate Explanations

America added 194,000 jobs on net in September, an appalling figure relative to the consensus forecast of 500,000. This represents the second consecutive month that job growth fell well below expectations, strengthening the case that this is not simply statistical aberration. U.S. payrolls remain approximately 5 million jobs short of pre-pandemic levels, and at September’s pace it will require another 26 months to reach full recovery.

The unemployment rate fell to 4.8% in September, but it fell for all the wrong reasons. The size of America’s increasingly flaccid labor force declined by 183k people for the month. Between you and me, the U.S. labor force could use the participation rate equivalent of a good dose of Viagra (now my second favor Pfizer product), or perhaps a hardy generic substitute.

Education and health segments were utterly pummeled. Public schools collectively shed 160,800 positions while educational services lost 18,900 jobs and the healthcare sector lost another 17,500 jobs. Many of the implicated occupational categories are female-dominated, and if you keep reading you will appreciate the salience of that.

These categories are likelier than most to be subject to vaccine mandates, and it would be easy to blame the lackluster payroll report on vaccine hesitancy. While that may very well have contributed to job losses in these segments, I think there’s a better, albeit more technical explanation. Get ready to go deep into the weeds with me as we frolic amidst the data.

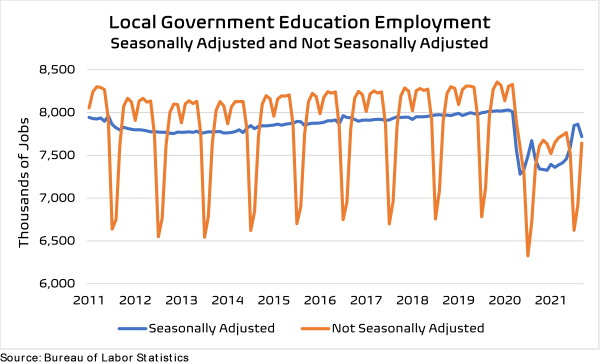

The payroll data you hear discussed is virtually always seasonally adjusted. Seasonal adjustments, explained as simply as possible, are alterations to the data that render them comparable on a monthly basis. For instance, on a not-seasonally adjusted basis, the retail sales segment adds jobs rapidly leading up to Christmas and then loses about 585,000 jobs each January as retailers predictably pare down their respective workforces after the holiday season. The chart below supplies a decent visualization of how these adjustments work.

Each year, public school employment declines rapidly in June and July as students declare their freedoms, bid adios to their former teachers, sing Pink Floyd songs, and get ready to unleash madness and mayhem upon their communities. This year, however, the dip in July employment levels wasn’t as sharp as usual, so the seasonal adjustments made July look like a period of job growth (which it wasn’t – all of this is statistical make-believe).

Correspondingly, the increase in September hiring wasn’t as significant as usual, and so when the seasonal adjustments were applied to that month, it looked like we had let go of many educators, which of course we didn’t. In other words, at least some of September’s woeful performance is attributable to the artificially boosted numbers of prior months. I don’t know about you, but I find this type of discussion incredibly revealing and arousing.

Now don’t get me wrong. The reluctance of would-be jobseekers remains a major reason for lackluster job growth. America continues to be associated with many job openings. If only we could get the workforce excited about the prospect of reentering the job market. Working in conjunction with the delta variant and attendant global supply chain disruptions, the result has been pervasive input and output shortages and rapidly rising prices. I had expected the second half of this year to bring explosive growth, but it just hasn’t happened.

That said, nonresidential construction managed to add jobs in September just as contractors had been predicting, and you can read my in-depth thoughts regarding that at Associated Builders and Contractors.

Three Key Takeaways

The number of women in the labor force declined by 296,000 in September, while the number of men increased by 113,000. The female labor force is currently 2.5% smaller than February 2020 levels, while the male labor force is 1.3% smaller.

The unemployment rate for workers with less than a high school diploma increased in September, while the unemployment rate for everyone else fell. The labor force participation rate for those without a high school diploma fell significantly more than for all other levels of educational attainment combined (are these folks more resistant to vaccine mandates?).

According to household data, the number of Americans with full-time jobs increased by 591,000 in September, while the number of Americans with part-time jobs fell by 36,000.[1] This makes it all the more likely that at least some of the employment weakness embodied within the establishment data are attributable to statistical adjustments.

What to Watch

Supply chains, inflation, labor shortages.

[1] Household data come from the Current Population Survey—the source of unemployment data—which surveys households instead of employer payrolls. The household data showed significantly faster hiring than the payroll data in September, though the payroll data is generally considered a more reliable source.