A lot to get through this time around—this combines the September and October Q&A, and a bunch of you had questions about the Fed and interest rates (which you can brush up on in our very basic primer).

So this post has 14 answers from Anirban and 3 from Zack. We’ll send out a request for questions at some point in November, but feel free to leave your asks in the comments (or send them to us directly by replying to this email).

As a reminder, we’ll have our Week in Review post out on Friday for paying subscribers. The big data releases this week are third quarter GDP and the PCE Price Index (a primary measure of inflation). If you’re not a paying subscriber but want to be, just click the link below:

Anirban’s Answers

Can you explain why 2% is the magic, perfect rate of inflation?

The Fed justifies it as the rate “most consistent with the Federal Reserve’s mandate for maximum employment and price stability.” If they tried to maintain a 0% rate of inflation, that would create a constant risk of deflation, but 2% creates a buffer. Moreover, at 2%, prices double every 36 years or so. That’s really manageable. If inflation were 4%, then prices would double every 18 years. Big difference, yes?

Is the U.S. smart or stupid for borrowing so much money?

We are stupid for borrowing so much money insofar as we tend to misspend it. A lot of money spent during the pandemic has gone *poof* with nothing really to show for it. I’m pleased that we’re spending on infrastructure, of course, but we haven’t found an adequate permanent funding source for that, which means that while at least some of that money is well spent, it’s also increasing the national debt.

What is a “Healthy” Unemployment rate? Given current economic environment, what’s our target unemployment rate that would indicate a healthy and stable level?

The lowest possible unemployment rate that keeps inflation down. Right now, 3.5% is too low; we may need to get into the 5%-range before things settle down. After that, I think we can get back to 4% or less without triggering much inflation based on the experience of the late-90s and late-2010s.

Janet Yellen said, “we are worried about a loss of adequate liquidity in the market” when discussing US Treasury Securities. Why is this happening and what will be the ramifications?

Since investors expect rates to keep rising, people are less willing to purchase Treasuries and perhaps other bonds. Of course, rising rates mean that the underlying value of a bond declines. If everyone believes the same thing, that bond values will decline, there won’t be enough people to buy them at current interest rates, which means that interest rates could take off (They already have, right?).

How does the strength of our currency impact the Fed’s current playbook?

A stronger U.S. dollar helps keep import prices low, which in turn helps the Federal Reserve. Remarkably, despite the runup in the value of the dollar against virtually every currency, inflation remains high. That gives us a sense of how much the Fed overdid stimulus. Inflation could be even worse but for the strong U.S. dollar.

How long does it generally take for interest rate hikes to work their way into the economy?

The first impacts can be immediate (looking at you, housing market), but the cumulative effects often require up to 18 months to play out. With the Federal Reserve in the midst of raising rates, it may be quite a while before the U.S. economy begins to expand rapidly again.

What are your thoughts on the Quantity Theory of Money (QTM) and how that plays into a lagging fed?

The QTM is a theory dating back to the early 1500s that states that price levels will increase proportionally with the money supply. Well, M1 (currency in circulation and checking accounts) increased 372% between February 2020 and the peak in January 2022, while M2 (which is M1 plus savings accounts, money markets funds, etc.) increased 28.7% over that span. Overall inflation was 8.9% over that span and 14.6% from Feb-20 to Sep-22.

That’s MV=PY at work! (M=money supply, V=velocity of money, P=price level, and Y=real GDP). Velocity is often treated as a constant, so what this means is that when money supply increases, Q (economic growth) and/or P (prices) accelerate. We got both, which is why the economy looks and feels overheated.

Now the Fed is tightening the money supply, but the growth slowing process operates with a lag. Hence the fear that they will overtighten, not waiting long enough for past interest rate increases to work their magic. My prediction remains that the Fed will drive us into a non-trivial recession.

Does heavy industry give the public unrealistic expectations on its ability to address climate change? Has public outcry on an issue like this ever led to REAL political change?

I have no idea if heavy industry or big corporations are over-promising. But I can see that GM, Ford, and many others are really taking net zero goals seriously. I think public outcry can generate much progress, including on eliminating child labor, improving working conditions, diminishing excessively high tax rates, giving women the right to vote, civil rights, etc. Of course, if public outcry calls for moving our society in the wrong direction, that can have an impact, too.

Is the fed actually effective? Does the approach need to be considerably changed or the mandate amended?

A Fed can be effective. See Volcker (heroic effort to bring America low inflation and low interest rates that prevailed for decades), Greenspan (not perfect, but cautious), and Bernanke (just plain brilliant Nobel Prize winner and policymaker). But the current Federal Reserve is not effective, in my opinion. I have no problem with the dual mandate of maintaining 2% inflation and as close to full employment as possible. The current Fed missed the mark, and the entire world is suffering because of that as borrowing costs explode and economies collectively head into recession.

If you were a commercial subcontractor in the DMV, what would you do now to prepare for the next three years in construction?

I would market heavily to owners of underperforming buildings who are desperate to raise occupancy and stabilize rents. That requires repositioning buildings in the marketplace, often by rendering improvements to common areas, investing in HVAC and other things to render a place more appealing. There will be many tenants on the move over the next few years as current leases expire, so while new construction will take a hit, there may be an opportunity for subcontractors to help improve many properties in the DMV.

Thoughts on a proposal to tax $500k+ houses in Garrett County to fund the first-time home buyers program as a way to address work force issues?

Silly. Those homes pay a lot of the County’s tax bills. The people who reside there, whether permanently or seasonally, drive a ton of local business activity. Killing the goose that lays golden eggs is just not a good idea. If anything, the County should find ways to expand the number of high-priced residences to generate more revenue to invest in high school CTE programs and in Garrett College.

Note from Zack: As of August, the average sale price in Garrett County was $678k and the median was $528k, so this proposal would apply to a whole lot of homes. More data available at Maryland REALTORS.

According to the Baltimore Banner, Baltimore City is losing $200MM from vacant properties. What can we do as individuals to push to change this?

Vote for competent politicians. We haven’t done that for a while, at least not enough of us. The number one owner of property in the City is the Mayor & City Council. They need to accelerate the process of turning over properties to private investors. Obviously, reducing crime and other quality of life detriments will be critical to reversing population decline. I was pleased to see that City test scores held up pretty well in recent years even as other communities have experienced substantial declines in reading and math scores.

How will the recession you’re predicting impact tourism in the Orlando and North Miami beach area?

Consumer discretionary spending generally gets hit hard during downturns, and I predict tourism-related spending will fade next year. Americans have been spending a lot on catch-up leisure travel this year, but as their balances have slid lower, they’ll spend less on travel too. So the outlook for Orlando and the North Miami beach area is not great. Moreover, both those economies have benefitted from a red-hot housing market, and with mortgage rates at their highest level in decades, that’s no longer the case.

When will the Orioles win a pennant?

2025. World Series victory, 2026.

Zack’s Answers

Where have all the workers gone?

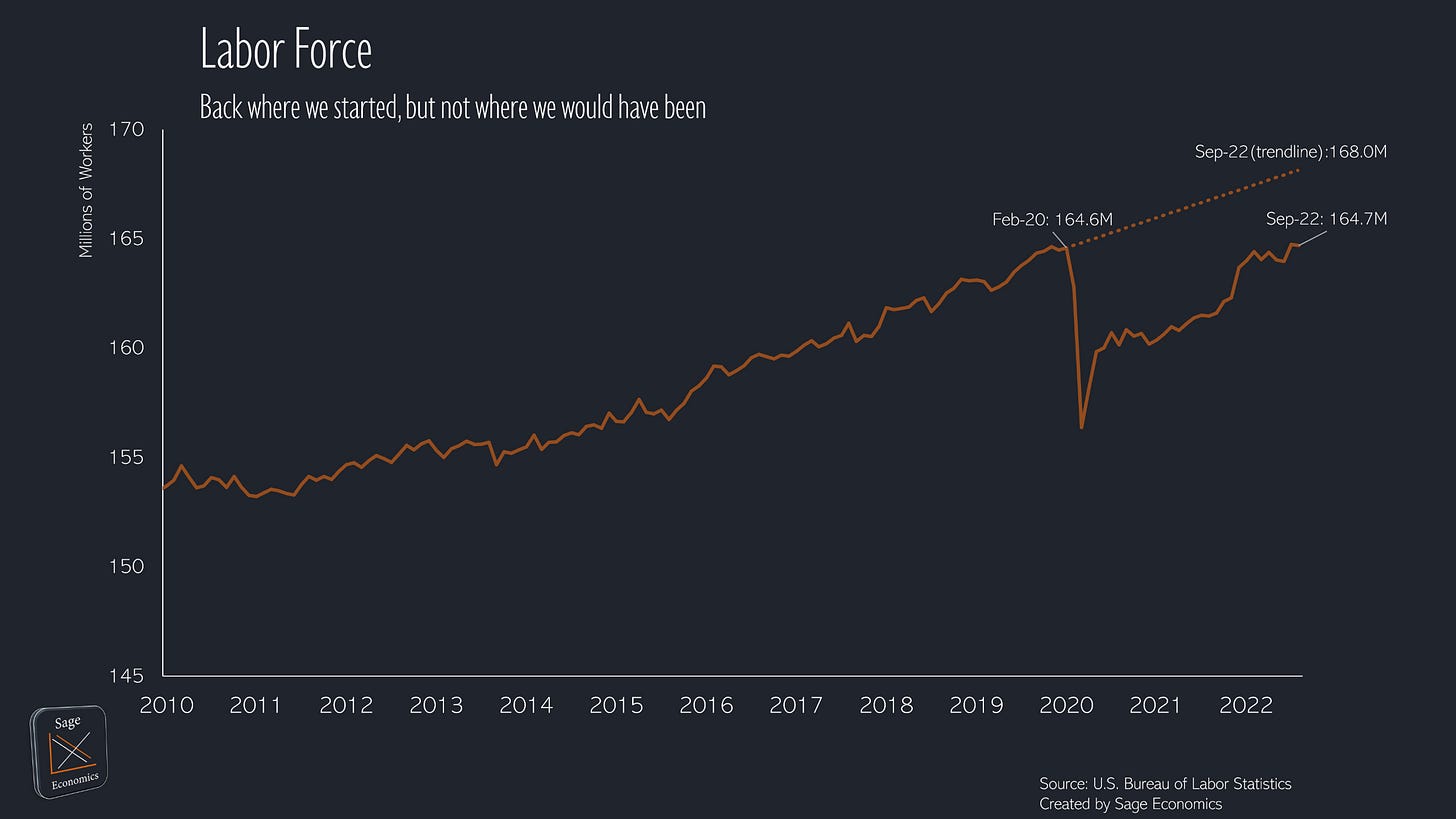

This is a toughie. Based on a very back of the envelope trendline (see below), the economy has about 3.3 million fewer workers than it would have given pre-pandemic trends.

Where have they gone? Let’s start with retirements. Unfortunately, there’s not great data on retirement (you don’t have to register your retirement or anything), so you get a lot of researchers producing their own estimates based on Current Population Survey data. This article, for instance, references data produced by Indeed and the Economic Policy Institute. The problem with those proprietary estimates is they’re produced once and not updated, so it’s not great for monitoring over time.

Looking at the U.S. labor force aged 55+, we see that it’s about 0.8% smaller than it was pre-pandemic, and the labor force aged 65+ is actually larger than it was in February 2020. It’s quite possible that a lot of people retired early in the pandemic, but it’s also quite possible that inflation, lower asset values, and a worker-friendly hiring market induced a lot of those retirees back into the workforce.

Then there’s immigration. The U.S. had about 500,000 foreign born immigrations in 2021, based on Census Bureau data, well below the average of 1.3 million from 2010 to 2019. The U.S. issued 168,000 work visas in 2021, 59% fewer than in 2019. If we issued visas at the 2019 rate in 2020 and 2021, there would be about 1.1 million more potential workers in the U.S.

Finally, let’s look at prime age Americans because, you know, nobody wants to work anymore (to be clear, I think a majority of people never wanted to work in the first place and worker motivation isn’t a real factor here). The prime age (25-54) labor force participation rate was 82.7% as of September, just below the February 2020 level but the same as in September 2019. Labor force participation for younger people (20-24) is down but still at the levels seen in 2014-2016.

Which is to say, beyond really low immigration numbers, we don’t have a great answer for this yet. The pandemic kicked up a lot of dust, and until it clears it’ll be tough to definitively answer these kinds of questions.

Is there a reliable estimate of the total amount of federal COVID relief funds appropriated and the percentage that actually been deployed?

There are a few sources for this, including: The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget’s COVID Money Tracker, or USASPENDING.gov’s tracker, or pandemicoversight.gov’s tracker.

Will 2023 be a good year for multifamily construction?

Probably. The owner-occupied market is completely frozen by the highest mortgage rates since 2002, and that’s turning a lot of would-be-buyers into renters. August 2022 saw the highest number of multifamily construction starts since 1985, and the past year saw the most authorizations for new housing units in buildings with 5 or more units since 1986. Assuming a normal share of those authorizations are converted into starts, multifamily construction should hold up fairly well in 2023 despite most economists now forecasting recession.