If an economics exam in 2019 asked, “What happens when inflation reaches a 9.1% annual rate in the middle of a 17 month period during which the Fed hikes rates 11 times to the highest level in 22 years?” and you answered, “employers add 320,000 jobs a month, unemployment stays in the mid 3% range, and consumers keep spending like crazy,” your professor would have hit you with a tack hammer.

You also would have been right. Despite a set of circumstances that by all accounts should have tipped us into recession (and still could), the economy keeps growing at a faster rate than anyone thought possible.

Literally anyone; an October 2022 WSJ survey of 74 professional forecasters predicted employers would add 21,000 jobs a month over the last third of that year. Actual job growth was 14x higher, and even the most optimistic of those 74 forecasters still undershot realized employment growth by more than 100,000 jobs a month.

How did professional economists miss this badly?

Broadly, economic forecasting is hard. Anything can upend an outlook; weather, domestic policy, the whims of mercurial authoritarian regimes, a ship getting wedged in the Suez Canal, etc. Even a team of national security experts, meteorologists, policy wonks, economists, shamans, and seers would have been completely wrong about the past couple years.

Specifically, a combination of unusual mortgage rate dynamics and surprisingly impactful policy has blunted the impact of higher borrowing costs and kept the economy growing.

Households just aren’t bothered by high rates

One way higher interest rates reduce economic activity is by increasing the interest payments homeowners make on their mortgages, but that hasn’t happened this time around. The reason: starting in the middle of 2020, a lot of people either bought or refinanced into mortgages with historically low fixed rates.

More than 1 in 5 outstanding mortgages are currently locked in at a rate less than 3%. Compare that to the start of 2020, when just 1 in 27 mortgages had a rate of less than 3%. A majority of mortgages (63%) are currently locked in at rates under 4%.

Despite average mortgage rates hovering near 7% for the better part of the past year, the share of outstanding mortgages with rates over 6% has actually fallen since the start of the pandemic.

And that’s just the homeowners with mortgages. About 42% of households own their homes free and clear, according to the Census Bureau’s American Housing Survey, up from about 34% in 2011.

So mortgage payments are low and fixed (or nonexistent) for most homeowners, but incomes are rising with inflation (and actually faster than inflation in recent months). As a result, mortgage debt payments currently account for just 3.9% of disposable personal income, the same (historically low) share as in Q1 2022 when the Fed started raising rates.

That’s kept pressure off of household finances which, despite inflation, are still in pretty good shape. That has a lot to do with the excess savings accumulated during 2020 and early 2021; Americans saved roughly the same amount in the first 12 months of the pandemic as they did in the three years leading up to it. With prices up and the savings rate down, some of that excess savings has been burned off, but enough remains to keep consumers spending.

But mortgages aren’t the only kind of interest payments, and personal interest payments (excludes mortgages) as a share of personal income has risen lately, up to 2.0% in May. Combined with the low mortgage burden, overall interest payments are still low by historical standards, but this is something to watch in the coming months.

The flipside of higher interest rates is that it also bolsters interest income, and the increase in interest expenses has largely been offset by an increase in interest income. Since the first rate hike in March 2022, personal interest income is up by $146 billion (annual rate), almost entirely offsetting the $154 billion increase in personal interest payments.

One important caveat: the people faced with higher interest expenses aren’t necessarily the ones receiving greater interest income. Because this data is only available in the aggregate, it’s likely that some households (especially those on the lower end of the income spectrum) are experiencing financial distress due to higher rates.

Big picture, however, households haven’t been particularly impacted by higher rates, and with private consumption accounting for about 68% of GDP, that explains a lot of the economy’s resilience.

Why is fixed investment holding strong?

Investment in structures and equipment, which accounts for about 12% of GDP, is generally more vulnerable to higher borrowing costs. All else equal, the rapid increase in interest rates should have caused a huge contraction in investment activity.

But all else isn’t equal. Monetary policy, controlled by the Fed, has been contractionary, but fiscal policy, controlled by legislators, remains extremely expansionary—think infrastructure spending, the Inflation Reduction Act, the CHIPS Act, ongoing student loan pauses (more on that below), etc.

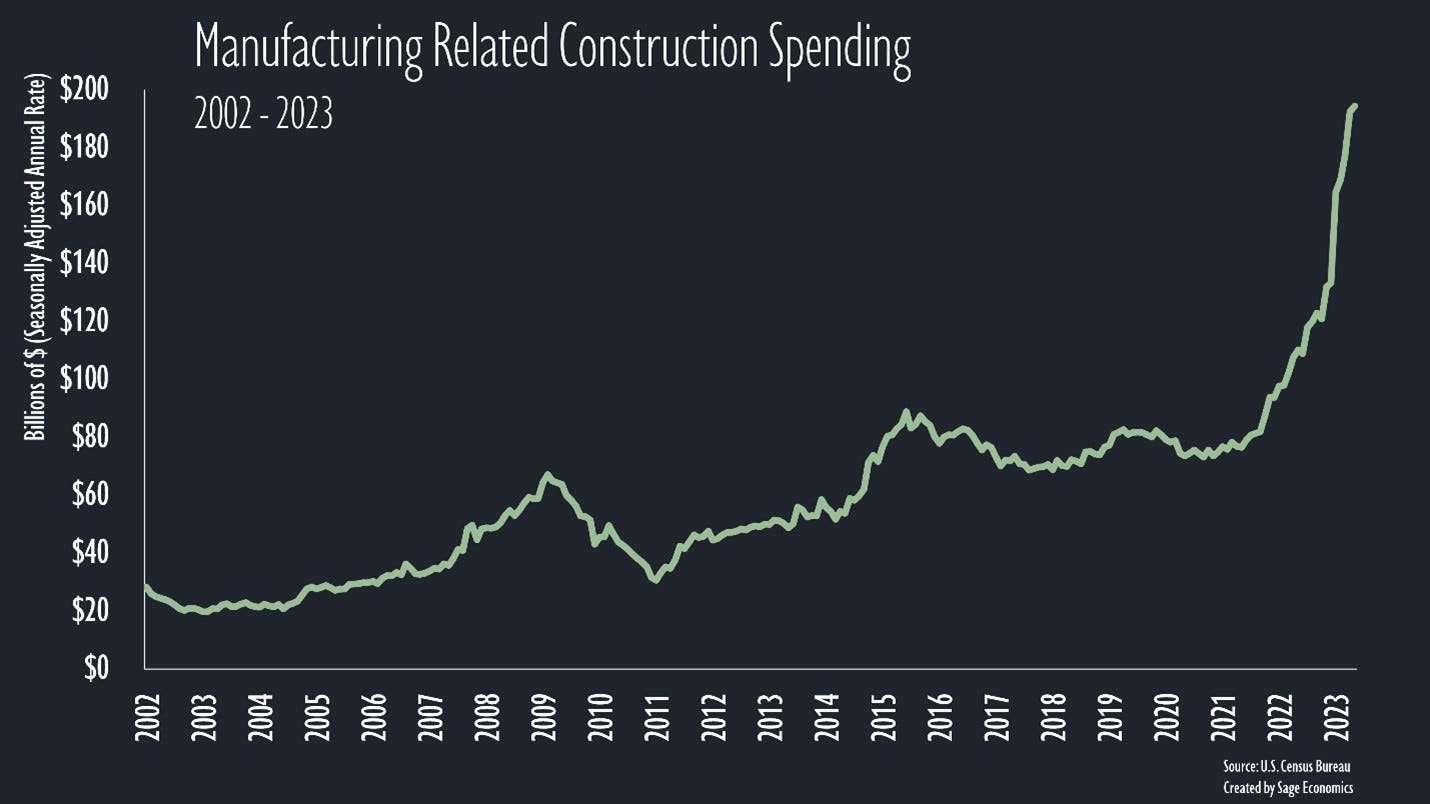

Consider manufacturing-related construction spending, which is up a staggering 154% over the past two years due in large part to the IRA and CHIPS Act. That alone counteracts a lot of the weakness in privately financed segments.

And there has been weakness. Private construction spending is unchanged over the past year even including the massive increase in manufacturing-related spending, and that’s before accounting for inflation. Public construction spending, on the other hand, is up 12.3%.

The Fed is trying to slow the economy to push inflation back to 2%, while legislators are enacting policy that’s done the exact opposite of slowing the economy. This means rates may have to go higher and stay there longer to conquer inflation, but it also makes a recession less likely in the short term.

Where could things go wrong from here?

Certain parts of the economy, like housing, have been crushed by higher interest rates. Spending on residential construction, for instance, is down more than $111 billion since the middle of 2022.

The goods side of the economy is also floundering, though that might have more to do with a reversion to a pre-pandemic balance between spending on goods and services and less to do with interest rates. Industrial production is down since the start of the year, and manufacturing and truck transportation employment have essentially flatlined. The latter could really buckle in the coming weeks as Yellow, the fifth-largest trucking carrier, faces a looming Teamsters strike and quite possibly bankruptcy.

Credit card debt could also become a problem. At the end of the first quarter, delinquency rates on credit cards were still historically low at just 2.4%, but with interest rates on credit cards surging to the highest rate since at least 1996, even a modest increase in delinquency could have a punishing impact on consumers.

Speaking of credit, credit conditions have tightened significantly since the failure of multiple banks earlier this year, and that has and will continue to reduce investment.

Then there’s the looming resumption of student loan payments. This will have some effect on consumer spending, but this thorough analysis by Apricitas Economics suggests the impacts may be smaller than expected: “…the administration’s student loan on-ramp plan provides extremely generous concessions for borrowers who have to resume repaying their loans—far from an immediate shock, the policy essentially allows consequence-free nonpayment for the first 12 months after payments officially restart.”

Maybe the biggest threat (and biggest unknown) is commercial real estate. Office buildings are worth a lot less than they were before the pandemic, and the interest only loans that finance them are coming due. Predictions on the fallout range from the owners of that debt taking a painful but survivable haircut to full blown financial collapse. The latter seems extremely unlikely, but there just isn’t great data on what’s happening here (we’ve been working on a longer post on CRE and might even get around to finishing it one day).

Finally, inflation is still a problem. We wrote about how inflation is almost certainly worse than it looked in the June CPI release, and alternative measures of inflation, like core CPI, Median CPI, and Sticky-Price CPI, all show prices increasing at a 4.8% or faster annual rate. Services prices are still increasing, and a lot of the worst of it is in difficult to avoid categories: car insurance prices are up 16.9% over the past year, and car repair prices are up 19.8%. Garbage collection prices are up 7.7%, and veterinarian prices are up 11.4%. Personal care (think services like haircuts) prices are up 6.5%.

Ongoing economic strength represents another risk factor on the inflation front—if demand stays elevated or picks up, another wave of inflation is a definite possibility.

The Upshot

If you need a reason to fret, we’ve been here before. This WSJ article from May 2008—titled Recession? Not so Fast, Say Some—starts:

A funny thing happened to the economy on its way to recession: It's taken a detour.

That, at least, is the view of a growing number of economists – including some who not long ago were saying a recession was all but inevitable. They note that stock and credit markets have steadily improved since the Federal Reserve intervened to keep Bear Stearns Cos. from bankruptcy in early March, while a series of economic reports have been stronger than expected.

To be clear, no one is predicting a recession anywhere near the severity of 2008, but unless everything we think we know about monetary policy is wrong, high interest rates will eventually catch up to the economy. When that happens, a shallow period of economic contraction still appears likelier than not.

What’s Next

This is a pretty busy week for economic data releases (not to mention the Fed’s interest rate decision later today). We’ll cover all of that in Friday’s Week in Review, which is only for paying subscribers.

as you work on you CRE analysis - its worth taking a look at the regional banks' slide decks from Q2 earnings releases/calls. Many of them brekadown office exposure in dollars and graphics. my quick take is the exposure isnt as great at the media theme has broadcast - though time will tell.