Have Trump's Tariffs Worked?

A six-month Liberation Day update

It’s been six months (and 50-plus changes to U.S. trade policy) since Trump made his economy-shaking Liberation Day tariff announcements. This post assesses how effective tariffs have been at achieving the stated goals of:

Raising revenues.

Shrinking the trade deficit.

Revitalizing U.S. manufacturing.

Providing leverage to negotiate freer trade.

Starting with the most successful one:

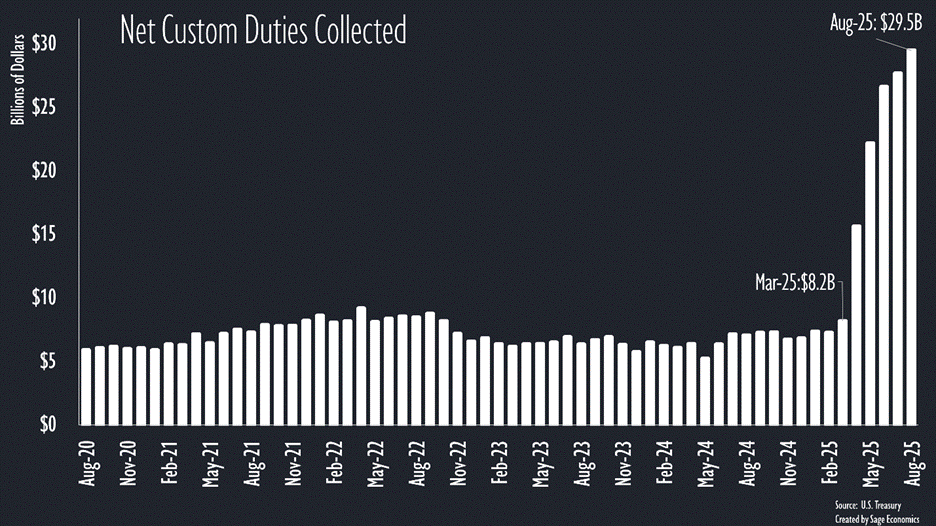

Revenue Generation

The U.S. has collected more customs duties in the 5 months since Liberation Day—about $122 billion—than in the 18 months prior.

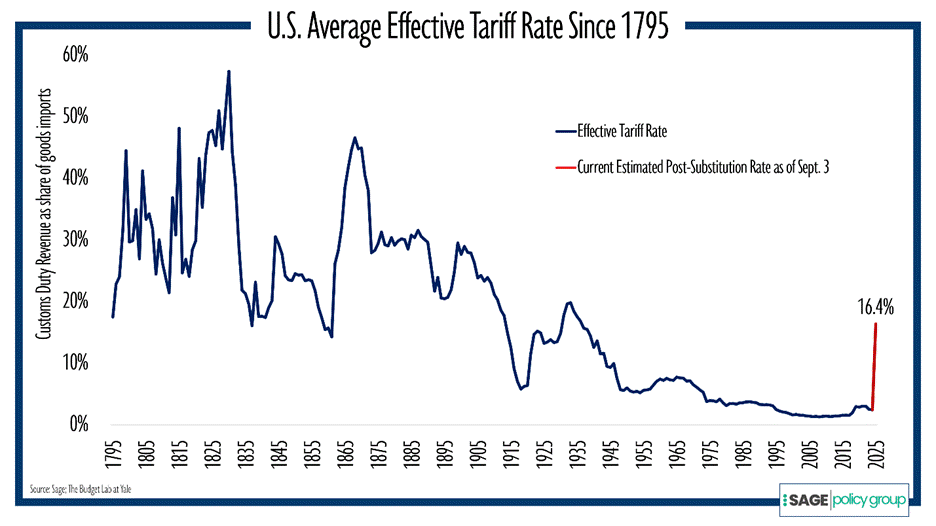

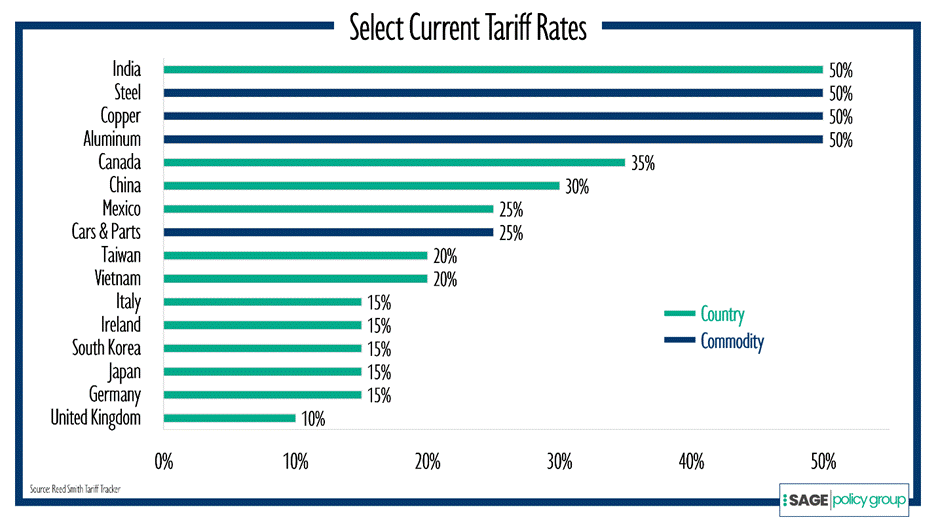

This isn’t much of a surprise. Higher tax rates mean more tax revenues, and our import tax rates are well above where they were. The current effective U.S. tariff rate is at the highest level since the 1930s.

While customs duties (i.e., tariff revenues) are up significantly, they represent a tiny share (well below 5%) of overall revenues. Notably, this won’t have any meaningful effect on the federal budget deficit, which inched down from $1.816 trillion (with a “T!”) in FY 2024 to $1.809 trillion in FY 2025 but is set to grow again next year.

It should also be noted that looking solely at customs duties overstates the revenue effects of tariffs, because 1) they lower other tax revenues by raising costs and 2) we’re going to use some of those revenues to bail out industries (like soy bean farming) that have been devastated by tariffs and trade disputes.

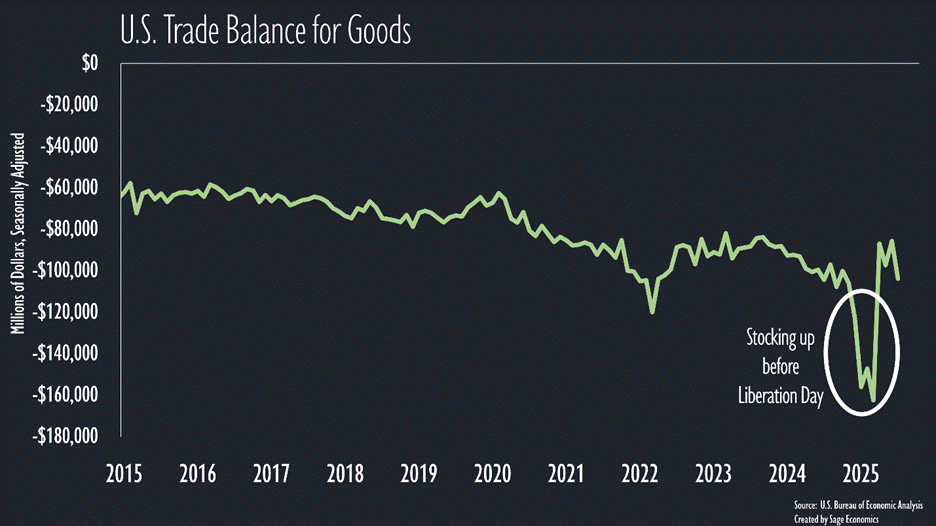

Shrinking the Trade Deficit

The U.S. buys more from other countries than they buy from us, and this difference is called the trade deficit. Our persistent trade deficit is possible because we run a capital and financial account surplus—the rest of the world buys more of our bonds, stocks, real estate, businesses, etc.

President Trump has been adamant about reducing the trade deficit: “You only have to look at our trade deficit to see that we are being taken to the cleaners by our trade partners…America has been ripped off by virtually every country we do business with.”

Have tariffs helped us close the trade deficit? So far, it’s complicated.

Companies, well aware of Trump’s tariff plans, raced to stock up on inventories/inputs at the start of 2025.1 This caused a massive expansion of the trade deficit (see the circle on the graph above).

It improved markedly in April, which reflects both Liberation Day and the fact that many imports were moved forward to the year’s first quarter. As of July, the monthly trade deficit is back to where it was at the end of 2024.

What do we take from all this? Not much. Supply chains can’t be dramatically altered in a few months. It takes years—decades, even—to shift production. Which is to say, don’t expect much change here.

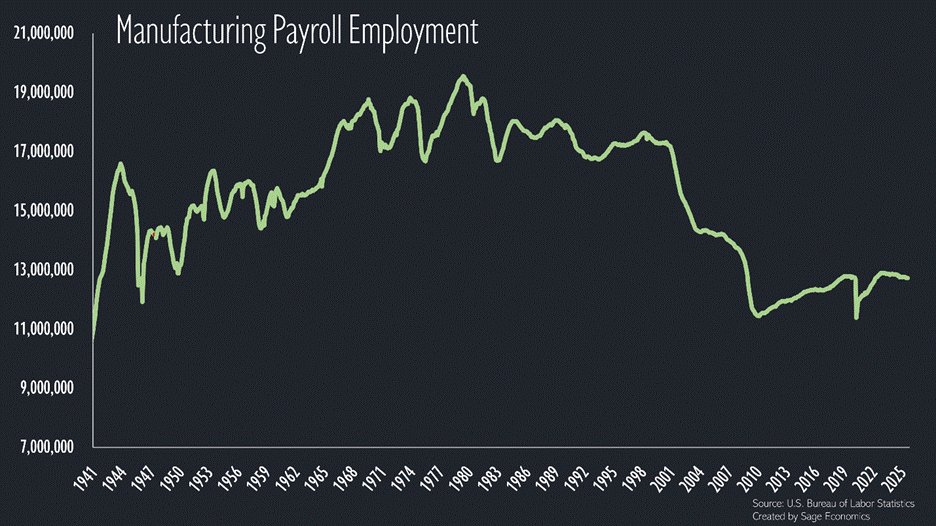

Revitalizing U.S. Manufacturing

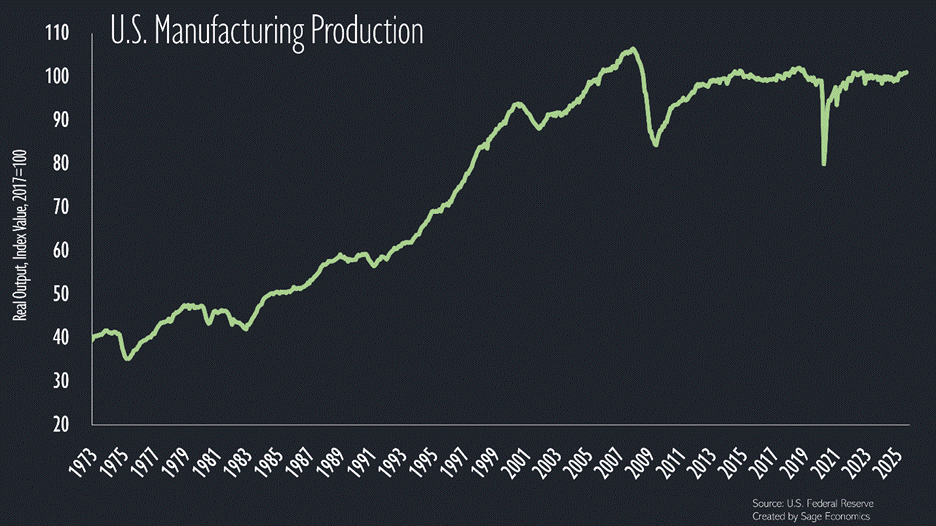

U.S. manufacturing employment peaked in 1979 and has been generally falling ever since. This isn’t just the outsourcing of production. Modern factories just require significantly fewer workers.

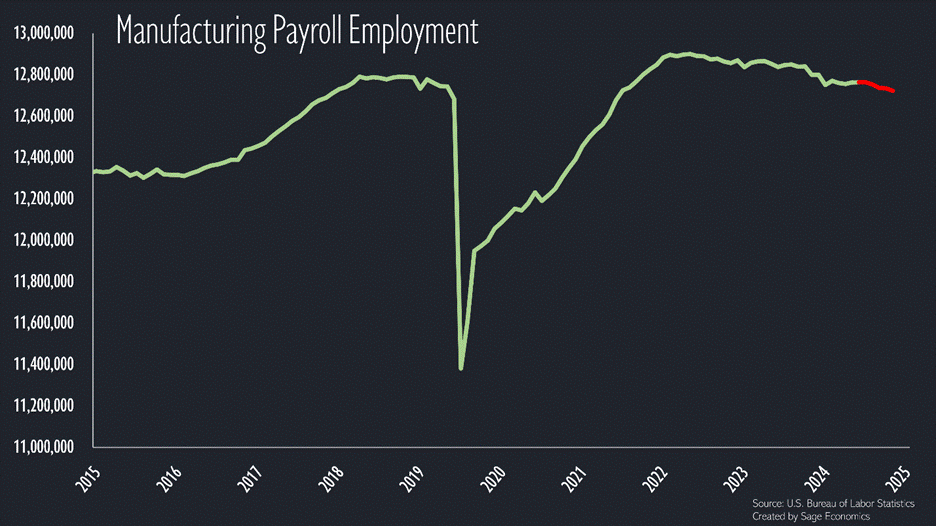

Zooming in to the past 10 years: we actually started losing manufacturing jobs (again) in early 2023. Have losses picked up since Liberation Day (the part in red)? Maybe a little. We’re down 42,000 manufacturing jobs over the past five months.

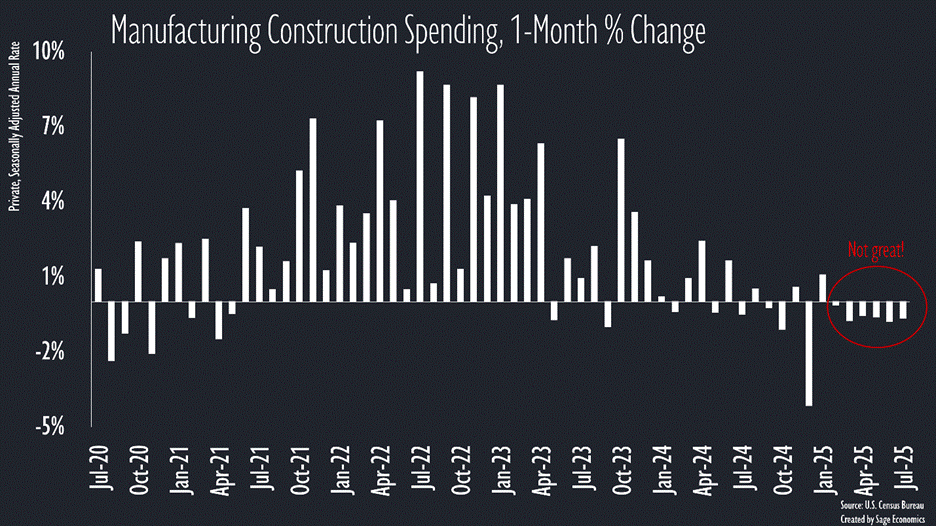

Whether or not tariffs have caused manufacturing job losses to accelerate, we certainly haven’t seen a manufacturing renaissance since Liberation Day, and it doesn’t look like one is coming. Manufacturing-related construction spending has fallen in each month since February.

Why would tariffs hurt U.S. manufacturing? Because about 50% of all U.S. imports are inputs to manufacturing. So if you operate a company that uses steel as an input and maintains factories in Brazil and the U.S., and there’s suddenly a 50% tariff on U.S. steel imports, you’ll probably shift production to your Brazilian plant.

This is exacerbated by poor policy design. Tariffs on inputs like steel and aluminum are currently higher than the tariffs on finished products, so it’s cheaper to build elsewhere and import than it is to import the raw materials and build here.

As a final note, the long term loss of U.S. manufacturing jobs has not coincided with a decline in U.S. manufacturing, and this is a long term trend. Modern manufacturing techniques mean fewer workers can make more things.

Trade Deals?

There’s not much to speak of here. We have a “Prosperity Deal” with the UK and “framework agreements” with the EU and Japan. Additionally, the White House put out a fact sheet on new procedures for establishing trade deals on September 5th.

It’s pretty clear that establishing a freer global trade regime is not the principal goal of U.S. tariffs.

What’s Next

We’ll cover all this week’s economic news and data—to the extent there is any with the government shutdown—in Week in Review, our every-Friday post that covers everything you need to know about the economy in a breezy, five minute read.

Week in Review is only for paying subscribers. If that’s not you and you want it to be, just click the subscribe button.

Increasing investor appetite for gold also drove up the trade deficit in these months.

Hi! What about travel/tourism in relationship to the trade deficit travel is traditionally considered to be an export to other countries