Quick Thoughts on Layoffs

Not as bad as they seem

You’ve probably seen headlines about layoffs: Amazon is cutting 18,000 jobs, Google 12,000, Facebook 11,000, and Microsoft 10,000. It’s not just tech. We’ve also seen layoff announcements from toymakers (Hasbro cutting 15% of its workforce), chemical companies (2,000 jobs at Dow), and paper manufacturers (3M cutting 2,500 jobs), among others. If the sticky note industry is struggling, what hope is there for the rest of us?

A lot, actually. The demand for labor was still strong heading into 2023 (which is as far as we have data), and you shouldn’t let anecdotal reports of layoffs change your mind about that.

Remember the Churn

Every month, you see headlines that say something like, “The economy added X jobs last month.” X has averaged 83,200 jobs over the first 22 years of the century and, outside of recessions, is usually in the range of 100,000 to 300,000.

Here’s the important thing about that headline number: it’s the net increase in jobs. Put another way, it’s the change in overall payroll employment. In November we had 153,520,000 employees, in December, 153,743,000. Some simple math gives us monthly growth of 223,000, which is that headline number that gets all the attention.

If we’re only adding low-six-figure jobs each month, the 51,000 layoffs at Amazon, Google, Facebook, Microsoft, have to make a big difference, right? Sure, they matter (especially for the people who are laid off), but the headline number is just the tip of the iceberg.

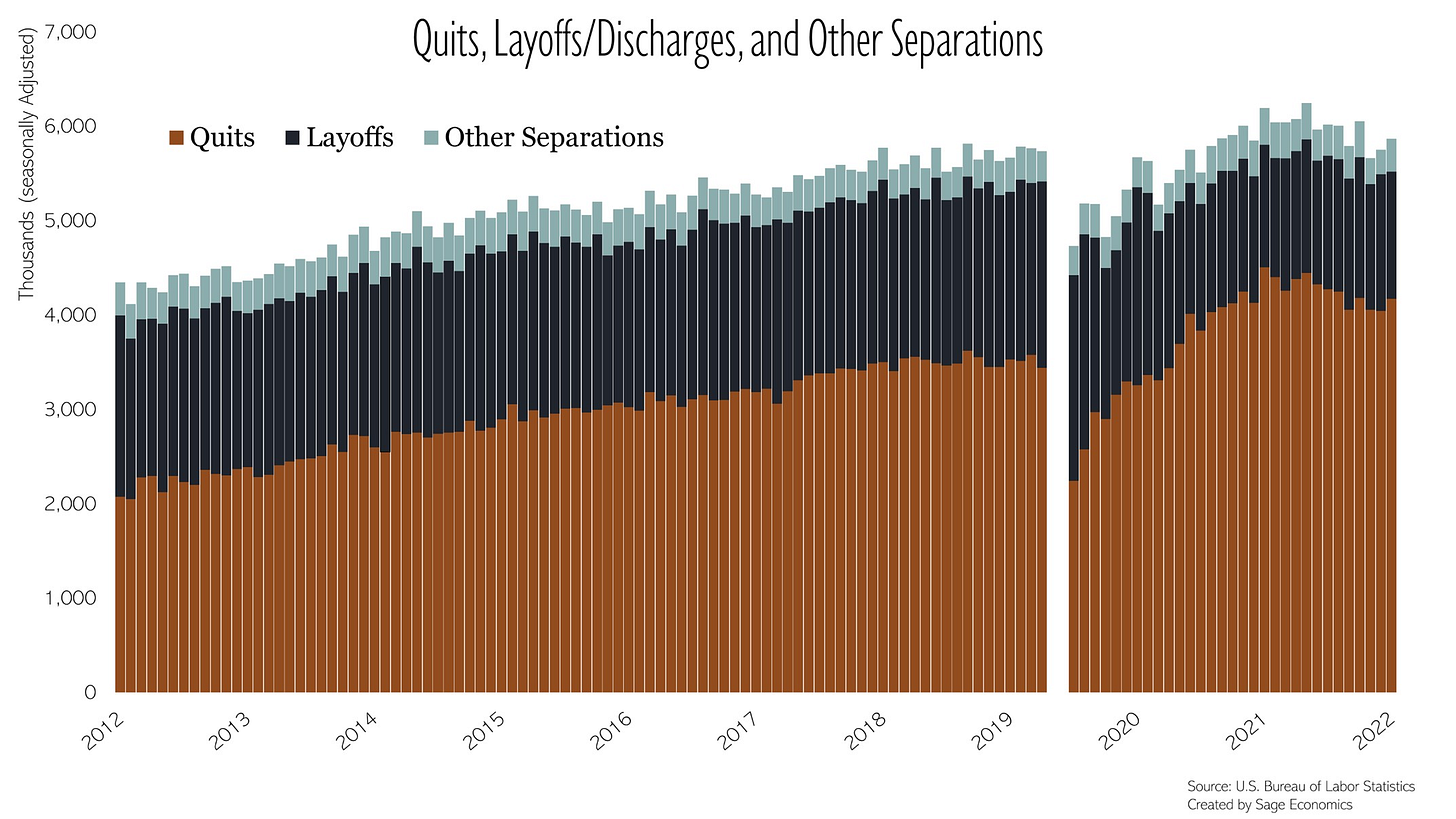

Let’s look at November 2022. That month, 4.2 million people quit their job, 1.4 million were laid off, and another 350,000 left their jobs for “other reasons.” Put those together, and we have 5.9 million separations (people who had a specific job but don’t anymore).

On the other side of the equation, about 6.1 million people got hired at new jobs in November. That comes out to about 250,000 net new jobs, but a lot happened under the surface.

When reading about layoffs, remember this monthly churn. About 1.4 million people have been laid off or discharged every month over the past year and a half, and that’s down from between 1.5-2.0 million each month in the years just before the pandemic. Those 51,000 combined layoffs at Amazon, Google, Facebook, and Microsoft equal about 3-4% of the layoffs that happen each and every month.

This graph shows you how many people separate from their job every month (excluding March and April 2020 because they’re annoying outliers that make graphs hard to read). Quits are up a lot since the start of the pandemic; there are lots of open jobs out there, and workers know they have choices. Because employers know that open jobs are hard to fill, layoffs are down.

There’s good news, too

Bad news gets more attention than good news, but there has been good news on the hiring front. Chipotle is adding 15,000 new workers. Boeing is hiring another 10,000 this year. These announcements were covered in major news outlets but drowned in the flood of scary layoff announcements.

There’s another reason the hiring hasn’t gotten as much attention as the firing. Large companies are dropping workers, and smaller companies, which have struggled to find workers since the start of the pandemic, are scooping them up.

According to ADP, the number of people working for large companies (500+ employees) fell by 151,000 in December, while the number working for companies with fewer than 500 employees increased by 386,000.

If one huge company cuts 10,000 jobs, it’s covered in the news. If 500 small companies each add 20 jobs, it’s not.

More specifically: when Microsoft layoffs off 10,000 workers, you hear about it. When most of those 10,000 workers quickly find work at smaller tech companies, you don’t.

Looking ahead

A majority of economists are predicting a recession at some point in 2023, and there are plenty of signs that the economy is weakening. Those signs, despite prominent layoff announcements, are not coming from the labor market.

Last week saw the fewest initial claims for unemployment insurance since April, and the unemployment rate still sits at 3.5%, tied for the lowest level since 1969.

We get a lot of new labor market data this week (I’m really tempting fate writing this post a few days before that new data is released.) The consensus forecast has payroll employment rising by a perfectly healthy 175,000 net new jobs in January and the unemployment rate inching up to a still extremely low 3.6%.

What’s next

We’ll cover the employment report in a post on Friday for all subscribers, and all the other economic data from next week in our Week in Review column, which we’ll also have out on Friday but is only for paying subscribers. Part II of our January Q&A should also be out soon, and you can read Part I here.

Great perspective Zack!

Isn't the unemployment rate a lagging indicator of recession?