June's Jobs Report: A Tale of Two Surveys

It Was the Best of Releases, It Was the Worst of Releases

Investors, economists, and others woke up this morning with great expectations. After two months of disappointing news on the labor market front, there was a sense that June’s jobs report would be different. The consensus estimate was that our nation added a bit more than 700k jobs last month. So when the number came in at 850,000, economists leapt in the air (by 1.5 inches on average—we don’t have great verticals) and started high-fiving as if one of us had hit a free throw in an actual competition.

It was premature celebration. As we started digging a bit deeper into the numbers, euphoria turned into puzzlement. While the government’s payroll survey indicated that the nation added a whole bunch of jobs, the household survey indicated that the nation lost 18,000 jobs in June. The unemployment rate rose to 5.9%, and the labor force participation rate remained stuck at an uninspiring 61.6%.

According to the data, the nation added and lost jobs in June. That’s David Copperfield-like magic. It defies the laws of science. What’s the twist?

Data embodied in the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ monthly Employment Situation report emerge from two distinct sources: 1) the Current Employment Statistics (CES) program, a monthly survey that produces estimates of employment, hours worked, and earnings based on the payroll records of businesses; and 2) the Current Population Survey (CPS), a monthly survey of households that has been conducted every month since 1940. This latter survey is used to generate estimates of unemployment, the unemployment rate, labor force participation, and a bevy of other labor market characterizing statistics.

Theoretically, these two surveys should generate some level of equivalency. After all, if a member of a households obtains a job, that should show up in both the household and payroll surveys1. But there was NO alignment in June, and that’s the kind of thing that can put one in a bleak place.

Here’s the secret. The household survey sucks. The household survey “is so volatile that it contains almost no additional information about monthly changes in employment.” Over time, the household survey is useful. It better be—that’s how we measure the unemployment rate. But data for individual months are just too noisy.

So the bottom line is this: June was a good month for job creation and supports the notion that economic recovery will be strong going forward. It will be the best of times.

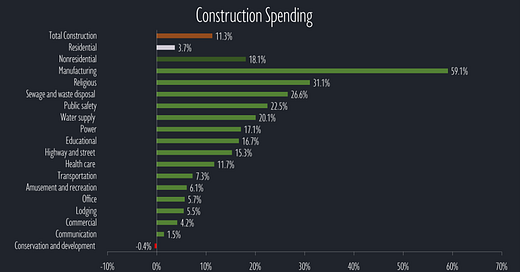

You can read more of my penetrating insights regarding the construction industry’s employment situation at Associated Builders and Contractors.

Three Key Takeaways

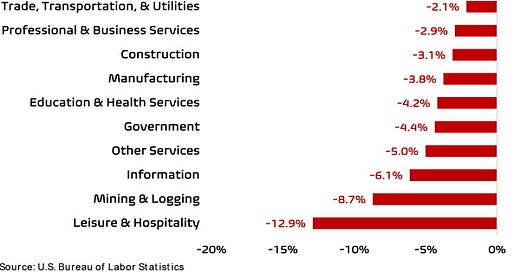

Leisure & Hospitality accounted for more than a third of June’s new jobs (343k), and the number of unemployed leisure and hospitality workers was down from 3.8 million in June 2020 to 1.5 million by June 2021. More than half the segment’s job gains came in the food services and drinking places category—that’s a fancy way of saying restaurants and bars. I can tell you from experience that if you drop the phrase food services and drinking places in a social setting, you will go home alone. The sub-segment added 194k jobs in June.

Computer chips—you can’t just eat one. Employment in the manufacturing of computers and motor vehicles segments declined by a combined 13.7k in June primarily due to an ongoing shortage of computer chips. This is largely why car prices are rising and you haven’t been able to purchase a Sony PlayStation 5 at an acceptable price. Food manufacturing employment also fell in June as many workers left for jobs in other segments. While we don’t anticipate a shortage of potato chips, food prices appear primed to increase in the coming months for a number of reasons, including worker shortages and elevated freight costs.

The U.S. Postal Service lost 3,200 jobs in June and has lost 7,100 jobs over the past year. While “neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed round,” it seems like congress can.

What to Watch

Expanded unemployment benefits expired at the end of June in many states. It will expire by September 6 in all states as students go back to school for in-person instruction. Is that when the economy really takes off?

But not in all cases. The household survey captures some forms of employment the CES doesn’t, like agricultural workers. This alone can’t explain June’s discrepancy.